- Tokenomics Fundamentals

- Understanding Token Supply

- Token Distribution Strategies

- Incentives & Web3 Flywheel

- Token Economy Dynamics

- Inflationary vs Deflationary Models

- Staking & Yield

- Exchanges, Liquidity & Market Making

- Designing Your Own Token Model

Tokenomics Fundamentals

Tokenomics refers to the economic model and framework that governs the use, distribution, and value of tokens. At its core, tokenomics is the study of the supply and demand of tokens, how they incentivise users and developers, and the role they play in driving network effects.

Unlike traditional currencies, tokens are highly versatile and serve a variety of functions. They can be used to access services, represent voting power, or even incentivise network participation. As the backbone of decentralised applications, tokens enable the creation of self-sustaining ecosystems where participants are aligned through incentives and governance mechanisms.

The success of a token model hinges on careful design. Token supply plays a critical role in determining scarcity and, by extension, value. Some tokens are designed with a fixed supply, mirroring the scarcity principle of assets like gold or Bitcoin. Others have inflationary models, where new tokens are continually minted to incentivise network participation or reward contributors. The decision to create a deflationary or inflationary supply is one of the most fundamental aspects of tokenomics, as it impacts long-term value and utility.

Beyond supply, the distribution of tokens is a crucial element in fostering a healthy ecosystem. How tokens are allocated between founders, early investors, and the public can greatly influence the perception of fairness and alignment of incentives. A well-structured distribution model ensures that no single entity holds disproportionate control over the token supply, promoting decentralisation and community engagement.

Effective tokenomics also relies on the careful alignment of incentives. Tokens are not merely static assets; they are dynamic tools designed to influence user behaviour. Incentives such as staking rewards, voting rights, and discounts encourage active participation within the ecosystem. These mechanisms help to bootstrap decentralised networks by rewarding users and developers for their contributions, while simultaneously increasing the overall value of the network.

The economic dynamics of tokens extend beyond just internal usage. Network effects are a powerful concept in tokenomics. The value of a token often grows as more users and developers participate in the network. A well-designed token model takes into account these network effects, ensuring that early adopters are rewarded for contributing to the system’s growth. This creates a positive feedback loop, driving more participants into the ecosystem and increasing the overall value of the network.

Tokenomics is more than just a technical or financial concept; it is the architecture that underpins decentralised economies. Its principles guide how value is created, distributed, and sustained within blockchain ecosystems. In an increasingly decentralised world, understanding the fundamentals of tokenomics is essential for designing effective, scalable, and sustainable systems.

Understanding Token Supply

The concept of token supply refers to the number of tokens that are, or will be, available within a given ecosystem. Understanding how supply influences a token’s economics is crucial for both developers and investors, as it affects scarcity, inflation, and overall market dynamics.

At the highest level, token supply can be categorised into two main models: fixed and inflationary. A fixed supply means that the total number of tokens is capped at a certain limit, creating a sense of scarcity similar to precious resources like gold. Bitcoin is a prime example of this model. With a maximum supply of 21 million coins, its scarcity is designed to drive long-term value as demand grows. In systems with fixed supply models, the relationship between supply and demand becomes more pronounced over time, often resulting in deflationary pressures as tokens become harder to acquire.

In contrast, inflationary token models have no predefined cap on supply. New tokens are continuously minted, often to reward participants, incentivise network activity, or secure the blockchain. Ethereum, for instance, employs an flexible, often inflationary model with no hard cap on the total supply, though recent updates have introduced mechanisms to burn or reduce tokens. While inflationary models ensure a steady flow of tokens to encourage participation, they must be carefully managed to prevent excessive inflation, which can erode token value and reduce the incentive for long-term holding.

The method by which tokens enter circulation is another crucial element of tokenomics. Tokens may be released all at once or gradually over time through various mechanisms. Initial token distributions, such as those seen in initial coin offerings (ICOs) or token generation events, usually involve a large portion of the supply being allocated to early investors, developers, or the founding team. Careful thought must go into this process, as imbalanced distributions may lead to centralisation or market instability. If too many tokens are concentrated in the hands of a few, the system risks becoming less decentralised, and market confidence can be shaken.

A more gradual release of tokens can help mitigate these risks. Models like vesting ensure that tokens allocated to team members or early investors are only made available after a specific period. This approach aligns long-term incentives and discourages short-term speculation. Token burning mechanisms, where tokens are permanently removed from circulation, offer another way to manage supply. This deflationary tactic is used to reduce total supply over time, potentially increasing scarcity and value. Binance, for example, implements regular token burns to reduce its circulating supply and support price appreciation.

Supply management also extends beyond just initial distributions and burning mechanisms. Minting, the process by which new tokens are created, is equally significant. Minting is commonly used in systems that require ongoing rewards for participants, such as proof-of-stake blockchains or decentralised finance (DeFi) protocols. In these systems, new tokens are minted to pay out rewards to stakers or liquidity providers. However, unchecked minting can lead to inflationary spirals, where the value of each token decreases as more tokens flood the market. Balancing minting with demand is key to maintaining a sustainable token economy.

The relationship between token supply and liquidity is another critical dynamic. A healthy market requires sufficient liquidity to enable smooth trading and price stability. Token supply directly influences liquidity, especially in decentralised exchanges or automated market makers. Low supply relative to demand can lead to high volatility, while excessive supply may result in low prices and sluggish market activity. Therefore, tokenomics often involves designing mechanisms that ensure adequate liquidity while preventing excessive dilution of value.

Token supply plays a significant role in shaping investor sentiment but there is no one right answer to how many tokens there should be. Fixed supply models often attract long-term investors who believe in the token’s deflationary potential, while inflationary models may appeal to those looking for short-term gains through staking or rewards. Understanding how supply influences market perception is crucial for designing token models that appeal to different segments of the blockchain ecosystem.

Token Distribution Strategies

Token distribution strategies determine who holds tokens, how they are incentivised, and how power and control are shared within the ecosystem. A well planned distribution model not only drives the initial adoption of a project but also ensures sustainable growth by aligning the interests of all stakeholders.

At the outset of a project, the initial allocation of tokens is a critical decision. Many projects choose to hold public sales, often referred to as Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) or Initial DEX Offerings (IDOs), to raise capital and generate interest. These public offerings allow early supporters to acquire tokens, often at a discount, in exchange for their financial contribution to the project. ICOs and IDOs provide immediate liquidity and enable projects to quickly bootstrap their development, but they also come with the risk of speculation, where buyers focus solely on short-term profit rather than long-term engagement.

The initial distribution also involves private allocations, often directed towards founders, development teams, and early investors. These stakeholders are vital in building the project, and their incentives must be carefully balanced. Large allocations to founders or investors can raise concerns about centralisation and control, especially if there are no mechanisms in place to lock their tokens. This is where vesting schedules play an important role. A vesting period ensures that tokens allocated to key contributors are locked for a certain time, encouraging long-term commitment to the project’s success. It prevents sudden sell-offs that could destabilise the token price and disrupt market confidence.

Airdrops are another popular distribution strategy. In an airdrop, tokens are distributed for free, either to existing token holders, early users, or participants in a community event. Airdrops are an effective way to raise awareness and encourage widespread token ownership. By decentralising the initial distribution and giving tokens to a larger number of users, projects can stimulate engagement and build an active user base. However, airdrops can also attract opportunists who sell their tokens immediately, causing short-term volatility. Successful airdrops tend to be carefully targeted and are often accompanied by a use case for the tokens, incentivising recipients to hold or use them within the ecosystem.

Beyond initial distribution, the design of ongoing token allocation is just as important. Many blockchain projects adopt reward-based distribution models, such as staking rewards or liquidity mining, to incentivise participation. In proof-of-stake systems, for example, users who stake their tokens to help secure the network are rewarded with additional tokens. This not only encourages token holders to engage with the platform but also helps maintain the network’s integrity. Similarly, in decentralised finance (DeFi), liquidity providers receive token rewards for contributing to liquidity pools, ensuring the smooth functioning of decentralised exchanges and protocols.

However, there are risks associated with these reward-based distribution models. Over-incentivising users through high token rewards can lead to inflationary pressures, where the constant issuance of new tokens dilutes the value of existing ones. Projects must strike a careful balance between providing attractive rewards and maintaining the token’s long-term value. Mechanisms such as token buybacks or periodic burns can help manage inflation by reducing the circulating supply of tokens over time.

Another key aspect of token distribution is the allocation of tokens for ecosystem development. Successful projects often reserve a portion of their token supply to fund future growth initiatives. These funds may be used to attract developers, support strategic partnerships, or finance marketing campaigns. By allocating tokens to these areas, projects can ensure they have the resources needed to continuously innovate and expand. Governance models, such as Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs), often play a role in deciding how these tokens are spent, giving the community a voice in shaping the future direction of the project.

Token distribution strategies must also account for market liquidity. A project’s tokens need to be easily accessible and tradeable to attract users and investors. Many projects choose to list their tokens on decentralised exchanges (DEXs) or centralised exchanges (CEXs) shortly after the initial distribution. Creating liquidity pools on DEXs allows users to trade tokens without relying on traditional order books, while listings on CEXs increase visibility and accessibility. Sufficient liquidity helps stabilise prices and ensures that the token can be used smoothly within its intended ecosystem.

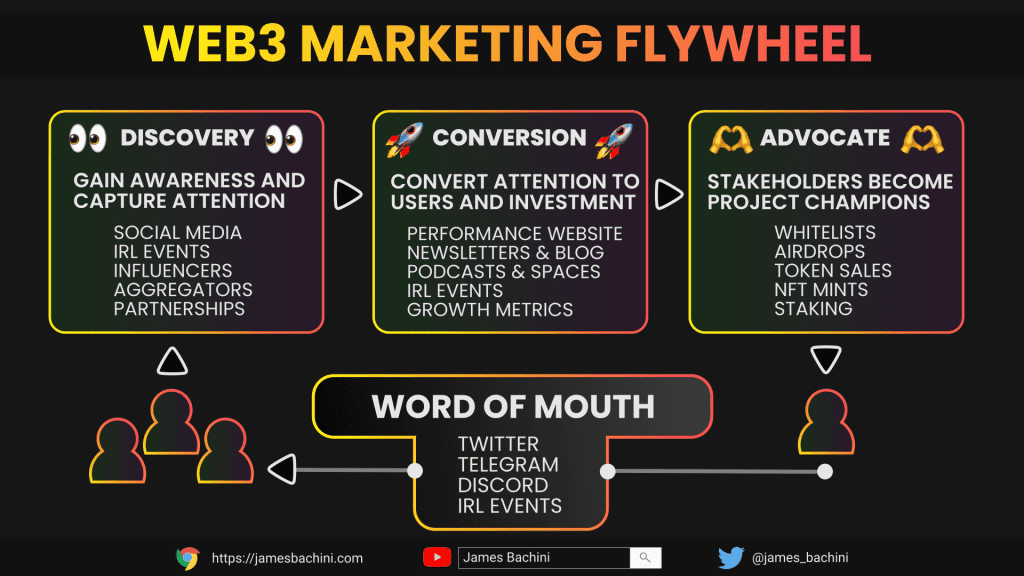

Incentives & Web3 Flywheel

In the world of Web3, incentives serve multiple functions. They encourage users to contribute resources, participate in governance, or provide liquidity. These activities are critical for the functioning of decentralised platforms, where reliance on centralised intermediaries is eliminated. Instead, tokens are used as a medium to reward participants, ensuring that they are compensated for their contributions to the ecosystem. This decentralised incentive structure is one of the key drivers of Web3’s appeal, as it aligns the interests of users, developers, and investors in a shared value network.

At the core of the Web3 flywheel is the principle of user participation. In traditional Web2 models, users contribute content, attention, or data without direct compensation. In contrast, Web3 shifts the paradigm by rewarding users for their contributions with tokens. These tokens can be earned through activities such as staking, validating transactions, or providing liquidity. The more users engage with the platform, the more valuable the ecosystem becomes. This increase in participation drives up the demand for the platform’s native token, creating upward momentum in its value. As token prices rise, so too do the rewards for participation, motivating even greater levels of activity.

The network effects that result from this cycle are what form the Web3 flywheel. In decentralised systems, the value of the network increases as more participants join, creating a positive feedback loop. New users attract more developers, who in turn build more applications and services on the platform. This expanded functionality encourages even more users to participate, reinforcing the growth cycle. Over time, this leads to a thriving ecosystem where the token’s utility and value are supported by the continuous expansion of the network.

Effective incentives are not merely about offering rewards; they are about creating sustainable and meaningful engagement. The challenge lies in designing incentives that balance immediate participation with long-term value creation. Short-term rewards can lead to speculative behaviour, where users join simply to extract value, only to exit when rewards diminish. To avoid this, token models must encourage deeper forms of engagement. This is where governance tokens come into play, giving users a stake in the future direction of the project. By aligning users with the long-term success of the platform, governance tokens incentivise them to stay invested beyond short-term rewards.

Another powerful incentive model in Web3 is liquidity mining. This strategy, pioneered by decentralised finance (DeFi) protocols, rewards users for providing liquidity to decentralised exchanges or lending platforms. In liquidity mining, users stake their assets into liquidity pools and are rewarded with the platform’s native tokens. This creates a strong incentive for users to supply liquidity, which in turn ensures that the platform remains functional and liquid. As more liquidity is provided, trading becomes smoother, attracting additional users and traders. The rewards from liquidity mining fuel the Web3 flywheel, as liquidity providers are incentivised to continue contributing, further reinforcing the network’s growth.

However, crafting incentives requires a careful balance between inflationary pressures and value creation. While issuing tokens as rewards can stimulate engagement, excessive token issuance can dilute value and lead to inflation. Projects must design reward structures that evolve over time, adjusting incentives to reflect the maturity of the ecosystem. Early stage projects may rely heavily on high token rewards to attract users, but as the platform stabilises, rewards should shift towards governance or staking incentives that promote long-term commitment and sustainable growth.

Incentives also play a critical role in governance. Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs), which are central to many Web3 projects, rely on token based governance to make decisions about the future direction of the platform. Governance tokens incentivise users to participate in decision-making processes, aligning the interests of the community with the project’s long-term vision. By giving users a voice in governance, projects can ensure that their incentives are not only focused on short-term engagement but are also driving the strategic growth of the ecosystem.

The self-reinforcing nature of the Web3 flywheel is its greatest strength. Once the flywheel is set in motion, well crafted incentives lead to continuous growth and value creation. Early adopters, attracted by rewards, become long-term participants who contribute to the platform’s success. As the platform grows, so too does the value of the token, which draws in more users, developers, and contributors. The challenge for Web3 projects is to ensure that this cycle remains sustainable and that incentives are designed with the long-term health of the ecosystem in mind.

Token Economy Dynamics

A well-designed token economy is the engine that drives the growth and sustainability of decentralised networks. The dynamics of token economies extend far beyond the mere creation of a digital asset. They encompass how value is created, distributed, and maintained within a blockchain ecosystem. Understanding these dynamics is essential for crafting token models that not only incentivise participation but also ensure long-term stability and growth.

At the heart of any token economy is the relationship between supply and demand. This interaction determines the token’s value and plays a key role in its overall success. On the demand side, tokens must serve a purpose within the ecosystem. Whether they grant access to services, enable participation in governance, or act as a medium of exchange, the utility of a token is the foundation upon which demand is built. The more useful the token, the more it will be sought after by users, developers, and investors.

Demand alone, however, is not sufficient to drive a successful token economy. Supply must also be carefully managed to balance inflationary and deflationary pressures. Projects must decide whether to cap their token supply or allow for continuous minting. Both approaches come with trade-offs. A fixed supply creates scarcity, which can drive up value over time as demand increases. On the other hand, inflationary models ensure that there is always a steady flow of tokens available for new users or participants. The challenge is to ensure that inflation does not outpace demand, which would erode the value of the token and disincentivise participation.

A healthy token economy must also account for token velocity. Velocity refers to the rate at which tokens are exchanged within the ecosystem. High token velocity can indicate active engagement, as tokens are continuously circulated between users, developers, and services. However, excessively high velocity can be a sign of speculation, where tokens are bought and sold quickly without meaningful engagement with the platform. This can lead to instability, with price fluctuations making it difficult for users and developers to plan long-term. Ideally, token velocity should reflect genuine activity within the ecosystem, balancing liquidity with steady, sustainable growth.

The network effects generated by a strong token economy are another critical dynamic to understand. In decentralised systems, the value of the network grows as more participants join and engage with the platform. This creates a virtuous cycle, where increased adoption leads to more utility, which in turn attracts more users. Network effects are particularly powerful in blockchain ecosystems because they are driven by decentralisation and user ownership. As token holders benefit from the growth of the network, they are incentivised to actively contribute to its success, further reinforcing its value.

One of the key challenges in managing a token economy is aligning the interests of different stakeholders. Founders, developers, investors, and users all play different roles within the ecosystem, and their incentives must be carefully balanced. Token allocation is central to this alignment. Early investors may be drawn to the project by the prospect of financial gain, while developers are motivated by the opportunity to build innovative decentralised applications. Users, on the other hand, are often focused on the utility that the token offers. A well-structured token economy ensures that all of these stakeholders are incentivised to contribute to the network’s growth without creating undue concentration of power or wealth.

Governance is another critical aspect of token economy dynamics. As decentralised networks grow, decision-making authority must be distributed among token holders. Governance tokens give users a say in the future direction of the project, aligning their interests with the long-term success of the network. The decentralised nature of blockchain governance ensures that no single entity can dominate the platform, fostering a collaborative environment where decisions are made collectively. This decentralisation of power is not only crucial for the platform’s resilience but also helps build trust among participants, reinforcing the network effects that drive growth.

A successful token economy must also be flexible enough to adapt to changing circumstances. Blockchain ecosystems are dynamic and constantly evolving, with new use cases, technologies, and market conditions emerging regularly. Token models that are too rigid may struggle to adapt to these changes, leading to stagnation or even collapse. In contrast, token economies that allow for flexibility in areas such as governance, supply management, and reward structures are better positioned to respond to new opportunities and challenges. This adaptability is key to ensuring the long-term sustainability of the network.

A subtle but powerful dynamic in token economies is the concept of stakeholder trust. Trust underpins every transaction and interaction within a blockchain ecosystem. Token holders must believe that the value of their tokens will be preserved or even increase over time. Developers must trust that the platform’s governance is fair and that their contributions will be rewarded. Users must trust that the services offered by the platform are reliable and that their data and assets are secure. A well-designed token economy fosters this trust through transparency, decentralisation, and robust governance mechanisms.

Token economies do not exist in isolation. They are part of the broader crypto and financial landscape, influenced by external factors such as market sentiment, regulation, and competition. As the adoption of blockchain technology grows, token economies will increasingly interact with traditional financial systems, requiring projects to navigate complex regulatory environments. Projects that are able to integrate smoothly with external systems, while maintaining their decentralised ethos, will be best placed to thrive in this new landscape.

Inflationary vs Deflationary Models

An inflationary model is one in which the supply of tokens increases over time. This increase in supply is typically achieved through a process known as token minting, where new tokens are created and distributed as rewards for network participation. Inflationary models are commonly used in proof-of-stake systems, where validators are rewarded with new tokens for helping to secure the network. Similarly, in decentralised finance (DeFi) protocols, liquidity providers often receive inflationary rewards for contributing capital to liquidity pools. The idea behind this approach is to incentivise continuous participation and ensure that there are always enough tokens circulating to meet the needs of the ecosystem.

The primary advantage of inflationary models is that they encourage active engagement. By offering rewards in the form of newly minted tokens, projects can attract users, validators, and developers, helping to bootstrap the network during its early stages. This dynamic is especially important for decentralised networks, where participation is voluntary and must be incentivised. Inflationary rewards ensure that contributors are compensated for their efforts, which can lead to stronger network effects and a more robust ecosystem.

However, the main challenge of inflationary models lies in managing the potential for dilution. As the supply of tokens increases, the value of each individual token may decrease, especially if demand does not grow at a corresponding rate. This can lead to inflationary pressures, where the purchasing power of the token diminishes over time. Projects that rely too heavily on inflationary rewards without ensuring that the ecosystem’s demand grows proportionately may struggle to maintain the value of their token. In extreme cases, runaway inflation can undermine the long-term viability of a project, eroding user confidence and discouraging further participation.

In contrast, a deflationary model reduces the token supply over time, typically through a mechanism called token burning. Token burning permanently removes tokens from circulation, often by sending them to a public address where they can never be accessed. Deflationary models are designed to create scarcity, driving up the value of the remaining tokens as the supply decreases. This scarcity principle is akin to the way finite resources like gold or land tend to appreciate in value over time due to their limited availability.

The key benefit of a deflationary model is its ability to support long-term value appreciation. By reducing the overall token supply, deflationary mechanisms create an environment where the token’s scarcity increases over time, assuming demand remains constant or grows. This can be a powerful incentive for users to hold tokens, as they anticipate future value growth. Bitcoin is perhaps the most well-known example of a deflationary asset. With its fixed supply of 21 million coins, Bitcoin’s scarcity is built into its very design, and this has played a central role in its rise as a store of value.

Despite its advantages, the deflationary approach comes with its own set of challenges. For one, deflationary models can sometimes discourage spending and participation. If users believe that the value of their tokens will increase significantly over time, they may choose to hold rather than spend them, reducing the overall utility of the token within the ecosystem. This phenomenon, known as hoarding, can limit the effectiveness of the token as a medium of exchange, particularly in platforms that rely on active participation and liquidity. Additionally, if the rate of token burning is too aggressive, it could lead to unintended scarcity, where users are unable to access enough tokens to engage meaningfully with the network.

A balanced approach that blends elements of both inflationary and deflationary models is often ideal. Some projects adopt a hybrid model, where new tokens are minted to reward participants while a portion of transaction fees or staking rewards is burned to counteract inflation. This allows for continuous incentives while controlling the total supply to prevent runaway inflation. Ethereum, for instance, introduced a mechanism through its EIP-1559 upgrade that burns a portion of transaction fees, helping to offset the inflationary issuance of new Ether and introducing deflationary pressure over time.

Ultimately, the choice between inflationary and deflationary models depends on the specific needs and goals of the project. Inflationary models work well for networks that require strong initial incentives to attract participants and foster growth. Deflationary models, on the other hand, are more suited to projects that prioritise long-term value preservation and scarcity-driven demand. It is essential for projects to carefully consider how these models align with their long-term vision and to be flexible in adjusting their approach as the network evolves.

Another factor to consider is how these models impact different stakeholder groups. Inflationary rewards tend to benefit early adopters and those who are actively involved in the network, such as validators or liquidity providers. In contrast, deflationary models primarily benefit long-term holders, as the reduced supply supports value appreciation over time. Balancing the needs of these different groups is crucial for ensuring a healthy and engaged community.

Staking & Yield

At its core, staking is a process by which users lock up a certain amount of tokens in order to support the functioning of a blockchain network. In proof-of-stake systems, validators are chosen to verify transactions and secure the network based on the number of tokens they have staked. The more tokens a validator stakes, the higher their chances of being selected to validate the next block. In return for this service, validators earn rewards in the form of newly minted tokens or transaction fees, providing them with a direct financial incentive to participate in network security.

The staking process helps ensure the integrity and decentralisation of blockchain networks. Unlike proof-of-work systems, which rely on computational power to secure the network, proof-of-stake systems depend on economic incentives. Validators are motivated to act honestly, as they stand to lose their staked tokens if they engage in malicious behaviour. This alignment of economic interest and network security is one of the key advantages of PoS systems, making them more energy efficient and scalable than their proof-of-work counterparts.

Staking offers token holders an opportunity to generate passive income by earning rewards simply for holding and staking their tokens. For users, staking represents a low effort way to earn yield while contributing to the stability and growth of the network. The yield earned from staking can vary depending on the network’s design, the amount of tokens staked, and the overall demand for participation. In general, larger stakes and early participation tend to result in higher yields, as these users take on more responsibility in securing the network.

The concept of yield has taken on broader significance with the rise of decentralised finance (DeFi). In DeFi ecosystems, staking has evolved beyond network security to become a key pillar of yield farming. Yield farming, or liquidity mining, allows users to stake their tokens in various decentralised applications (dApps) and earn rewards in return. In many cases, users provide liquidity to decentralised exchanges or lending platforms, facilitating trading or lending operations. In exchange for locking their tokens into these liquidity pools, they earn rewards in the form of governance tokens or a share of the platform’s fees.

Yield farming has proven to be one of the most attractive features of DeFi, as it offers potentially high returns in a relatively short period. By staking their tokens in different protocols, users can earn yields that far exceed those offered by traditional financial products. However, this comes with risks, such as the potential for impermanent loss in liquidity pools or sudden changes in token values due to market volatility. Despite these risks, yield farming has attracted a large number of participants, contributing to the rapid growth of the DeFi ecosystem.

Staking and yield generation have introduced a new dynamic to token economies. For one, they have increased the velocity of tokens within ecosystems, as users actively move their holdings between staking pools and yield farming opportunities. This constant movement can lead to increased liquidity and smoother price discovery, benefitting both users and platforms. However, it also introduces a layer of complexity, as participants must weigh the risks and rewards of different staking options and yield opportunities.

A significant benefit of staking is that it can align the incentives of long-term token holders with the growth and success of the network. By staking their tokens, users are essentially signalling their belief in the future of the platform, as they commit their assets to support its security and operations. This creates a powerful feedback loop: as more users stake their tokens, the network becomes more secure, attracting additional users and developers, which in turn drives demand for the token and supports its value.

The flexibility of staking mechanisms has also allowed for innovations such as delegated staking. In some PoS systems, users who do not wish to run a validator node can delegate their tokens to a trusted validator. In return, they receive a share of the rewards earned by that validator. This delegation model lowers the barriers to entry for staking, allowing more users to participate in securing the network without needing the technical expertise or infrastructure to operate a validator themselves. It also fosters a more decentralised system, as power is distributed across multiple validators rather than concentrated in a few large entities.

Despite the clear benefits, staking and yield farming are not without challenges. One major issue is the potential for inflationary pressures caused by high reward rates. If too many tokens are issued as staking rewards, the value of each token may decrease over time, undermining the incentive for participants to continue staking. Projects must carefully manage the balance between offering attractive rewards and maintaining a sustainable token supply. This often involves adjusting staking reward rates over time or implementing token-burning mechanisms to reduce supply.

One of the most interesting models in this field is the Curve Wars:

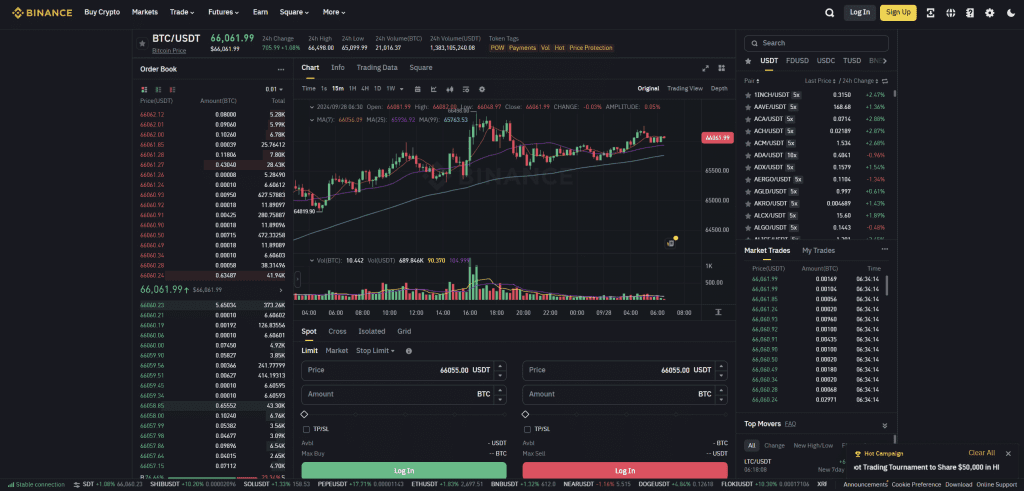

Exchanges, Liquidity & Market Making

Exchanges are the lifeblood of any token economy, providing the infrastructure through which tokens can be bought, sold, and traded. Without exchanges, token markets would lack liquidity, making it difficult for users to access and transfer tokens. Understanding the dynamics of exchanges, liquidity, and market making is crucial for ensuring the smooth operation of token ecosystems and fostering widespread adoption.

Exchanges can broadly be divided into two categories:

- Centralised Exchnages (CeX)

- Decentralized Exchanges (DeX)

Centralised exchanges are traditional trading platforms operated by third-party entities that facilitate the exchange of tokens. Users deposit their funds into the exchange, which acts as an intermediary to match buyers and sellers. Centralised exchanges have played a pivotal role in the development of the cryptocurrency market, offering high liquidity, ease of use, and access to a wide range of tokens. Major platforms like Binance and Coinbase are examples of CEXs that have become household names in the world of crypto trading.

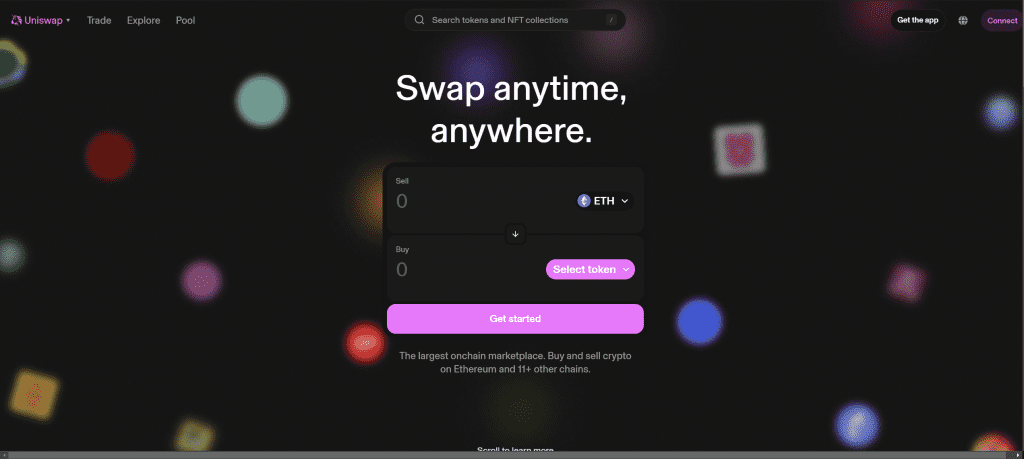

However, centralised exchanges come with certain limitations. Since they hold user funds, they are vulnerable to hacking or mismanagement, as seen in several high-profile incidents in the past. Moreover, centralised exchanges often face regulatory scrutiny, as they operate within the bounds of traditional financial systems. These factors have led to the rise of decentralised exchanges (DEXs), which operate without intermediaries and allow users to trade tokens directly from their wallets. DEXs, such as Uniswap and Sushiswap, use smart contracts to enable peer-to-peer trading, offering users more control over their assets and providing a higher level of security through decentralisation.

One of the most critical elements in any exchange, whether centralised or decentralised, is liquidity. Liquidity refers to the ease with which an asset can be bought or sold without significantly affecting its price. High liquidity ensures that tokens can be traded smoothly and at a stable price, which is essential for maintaining confidence in the market. In a liquid market, buyers and sellers can enter and exit positions with minimal slippage, ensuring that trades are executed at predictable prices. Without sufficient liquidity, token markets can become volatile, with large trades causing significant price fluctuations and discouraging participation.

In traditional financial markets, liquidity is provided by market makers—entities or individuals who offer to buy and sell assets at specified prices, thus ensuring continuous trading. In token markets, market making plays an equally important role. Centralised exchanges often rely on professional market makers to provide liquidity. These market makers profit from the difference between the buying and selling prices (the spread), while also facilitating efficient price discovery and reducing volatility. For newly launched tokens, securing the services of market makers is essential for building a stable trading environment and ensuring price stability.

In DeFi market making has taken on a new form through automated market makers (AMMs). AMMs eliminate the need for traditional order books by using liquidity pools to facilitate trades. Liquidity pools are smart contracts that hold pairs of tokens, enabling users to trade one token for another. Liquidity providers (LPs) contribute their tokens to these pools and, in return, earn fees from trades that occur within the pool. This decentralised approach to market making has revolutionised token trading by making it easier for anyone to provide liquidity and participate in the market-making process.

One of the primary innovations of AMMs is the concept of constant product market making, which is used by platforms like Uniswap. In this model, the ratio of tokens within the pool automatically adjusts based on trading activity, ensuring that liquidity is always available, regardless of market conditions. As more users trade within the pool, the prices of the tokens are adjusted algorithmically, allowing for efficient price discovery without the need for centralised intermediaries. This model has proven to be highly effective in fostering liquidity for a wide range of tokens, especially those that may not have access to professional market makers.

While AMMs have transformed liquidity provision, they are not without challenges. One of the key risks faced by liquidity providers is impermanent loss, which occurs when the price of tokens within the liquidity pool changes significantly from when they were first deposited. As prices fluctuate, liquidity providers may find that the value of their holdings has decreased compared to simply holding the tokens outside the pool. Despite this risk, the fees earned from providing liquidity can often outweigh impermanent loss, particularly in high-volume pools.

Liquidity is not just important for the smooth functioning of exchanges; it also plays a crucial role in token price stability. A token with low liquidity is more susceptible to price manipulation and volatility, as even small trades can lead to significant price movements. For projects, ensuring adequate liquidity is a top priority, especially in the early stages of token issuance. Many projects choose to allocate a portion of their token supply to liquidity mining programmes, where users are rewarded for contributing to liquidity pools. These incentives help to bootstrap liquidity, making it easier for users to trade and fostering greater participation in the ecosystem.

Another important factor in token liquidity is exchange listing strategy. Listing a token on a well-established exchange can dramatically improve liquidity by exposing it to a larger audience of potential buyers and sellers. Centralised exchanges, with their large user bases and deep liquidity, offer projects an opportunity to reach mainstream investors. However, the listing process can be costly, and exchanges often require projects to meet strict regulatory and financial criteria. For this reason, many projects initially launch on decentralised exchanges, where listing is more accessible, and liquidity can be quickly established through community participation.

In recent years, cross-chain liquidity has emerged as a significant development in the token economy. As blockchain ecosystems grow, there is increasing demand for the ability to trade tokens across different networks. Cross-chain bridges and decentralised liquidity protocols are being developed to enable seamless token transfers between blockchains, creating a more interconnected token economy. These solutions help to address liquidity fragmentation, where tokens are confined to individual blockchains, limiting their potential use cases and market size.

Designing Your Own Token Model

The first and perhaps most fundamental decision when designing a token model is defining its purpose and utility. Tokens can serve a variety of functions within an ecosystem, from acting as a medium of exchange or granting access to services, to enabling governance and decision-making. The token’s purpose must be intrinsically tied to the needs of the project and its users. A token without meaningful utility risks becoming merely speculative, attracting short-term traders rather than engaged users who contribute to the platform’s success.

Once the token’s purpose has been established, the next step is to determine the token supply model. Projects must decide whether to adopt an inflationary or deflationary approach, or a combination of both. Inflationary models may work well for platforms that require ongoing incentives, such as staking rewards or liquidity provision, where new tokens need to be continuously issued to encourage participation. However, managing inflation carefully is essential to avoid devaluing the token over time. Deflationary models, on the other hand, create scarcity by reducing the supply of tokens through mechanisms such as token burning. These models can drive long-term value appreciation, particularly if demand grows steadily alongside the diminishing supply.

The method of distributing tokens is equally important. Initial token distributions often set the tone for the entire project, determining who holds power and how incentives are aligned. A balanced approach to distribution can ensure that no single group—whether founders, early investors, or the public—holds disproportionate influence over the network. Many projects allocate tokens to early backers, team members, and the community in different proportions, with vesting schedules used to align the incentives of key stakeholders with the project’s long-term vision. Public token sales, airdrops, or liquidity mining programmes can also be employed to distribute tokens to a broader audience and decentralise ownership.

Incentive structures form the backbone of any token model, guiding user behaviour and driving adoption. These incentives can take many forms, from staking rewards and governance voting rights to discounts or exclusive access to services. The challenge is to design incentives that encourage meaningful and sustained engagement, rather than speculative trading. Governance tokens, for example, give users a stake in the future direction of the project, encouraging them to remain involved and take responsibility for the platform’s development. Similarly, staking mechanisms can incentivise users to lock up their tokens for extended periods, promoting stability and long-term participation.

An important consideration in any token model is the economic balance between supply and demand. Projects must ensure that demand for the token is continuously supported by the utility it provides, whether that utility is transactional, functional, or governance-related. If demand falls behind supply, the value of the token can erode, undermining the project’s viability. This balance can be maintained by periodically adjusting incentives, managing inflation, or introducing token-burning mechanisms to counteract excessive supply.

The governance model is another essential element of token design. Decentralised governance allows token holders to have a say in the future direction of the project, aligning their interests with the long-term success of the platform. Projects can implement decentralised autonomous organisations (DAOs) to give token holders the power to propose and vote on key decisions, such as protocol upgrades, fund allocation, or changes to tokenomics. This not only strengthens community engagement but also enhances trust, as decisions are made transparently and collectively. A well-designed governance system should be flexible enough to adapt to changing circumstances, ensuring that the project can evolve and respond to new opportunities or challenges.

Liquidity is another factor that must be considered when designing a token model. Tokens need to be easily accessible and tradeable for users to participate in the ecosystem effectively. Many projects allocate a portion of their token supply to provide liquidity on exchanges, ensuring that users can buy, sell, and trade tokens with minimal friction. Liquidity mining programmes, which reward users for contributing liquidity to decentralised exchanges, have become a popular method of bootstrapping liquidity, especially in the early stages of a project. By providing liquidity incentives, projects can encourage users to participate while also promoting price stability and smoother trading.

As the project matures, it is essential to monitor and adjust the token economy. Markets are fluid, and the needs of the ecosystem will evolve over time. The token model must be adaptable, capable of responding to shifts in demand, competition, or regulatory environments. Periodic reviews of the token supply, incentive structures, and governance frameworks will help ensure the long-term sustainability of the token economy. In particular, projects must be prepared to scale their token model as the network grows, expanding the scope of utility and ensuring that incentives remain aligned with the evolving needs of the user base.

Lastly, the legal and regulatory landscape surrounding token issuance must not be overlooked. Tokens, depending on their design and function, may fall under various regulatory frameworks. Understanding whether your token will be classified as a security, utility, or payment token is critical in determining the legal obligations you will face. Engaging with legal professionals and ensuring compliance with local and international regulations is essential to avoid legal pitfalls that could jeopardise the project.